Tag: search for identity

-

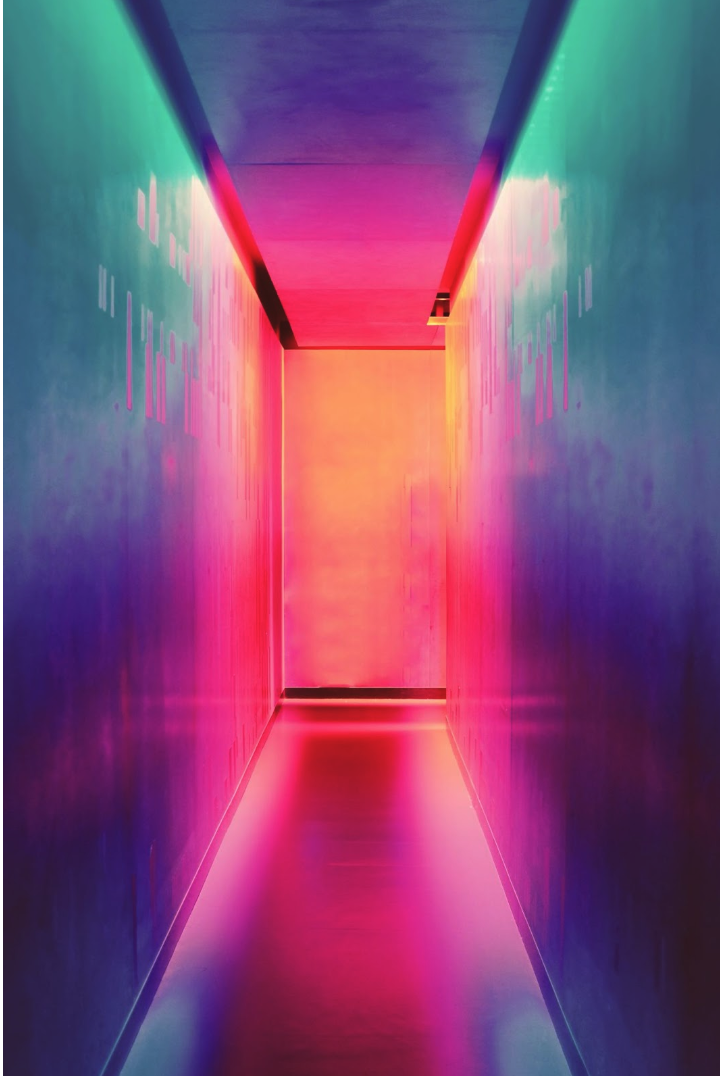

Ebony at K-Box Adoptee Takeover Night

—

by

in Adoptee Activism, Adoptee Artists, Adoptee Artwork, Adoptees Educate, Adoption Education for Adoptive Parents, Adoption Education for Professionals, Australia, Complexities in Adoption, Grief and Loss, Haiti, Importance of Connections to Origins, Lifelong Impacts of Adoption, Origins Search, Therapy, Transracial Adoption, Trauma in AdoptionEbony Hickey is a Haitian born intercountry adoptee to Australia whose contemporary artwork we included at the K-Box Adoptee Take Over Night.

-

Adoptee Review of Ra Chapman’s K-Box Play

—

by

in Adoptee Artists, Adoptee Artwork, Adoptees Educate, Adoption Education for Adoptive Parents, Adoption Education for Professionals, Australia, Complexities in Adoption, Grief and Loss, Importance of Connections to Origins, Korea, Lifelong Impacts of Adoption, Not Knowing in Adoption, Origins Search, South Korea, Transracial Adoption, Trauma in Adoptionby Kayla Curtis, Korean adoptee raised in Australia, social worker and counsellor specialising in adoption. I want to share some reflections from going along to the K-Box Adoptee Takeover Night at the Malthouse and seeing Ra Chapman’s K-Box play in Melbourne, Australia on 9 September. Personally, I am feeling an excitement from seeing K-Box because…

-

Integrating the Parts in Adoption

Bina shares about the fragmentation adoptees endure in order to survive and the grief work we must do to reintegrate our dual selves.

-

To Know Your Origins is a Privilege!

Lynelle shares the life experience of intercountry adoptees who don’t know anything about their origins.

-

From Thailand without an Identity

Lisa Kininger shares her lifelong quest to find her Thai identity. Along the way she discovers it’s the journey that matters, not the end result.

-

The Duality of being Disabled and Adopted

Erin shares the complexities of living with disability AND being an adoptee.

-

Little Question

by Pradeep adopted from Sri Lanka to Belgium, Founder of Empreintes Vivantes. Have you already made an appointment with yourself? I remember having to forge myself, like many adoptees! Forge my own personality without any stable benchmarks and this mainly due to the absence of biological parents. Indeed, children who live with their biological parents…

-

I’m an Immigrant, Voting in the USA

Mark shares mixed emotions after voting as an immigrant, adopted to the USA.