Tag: transition for older aged adoptees

-

A different type of Reunion

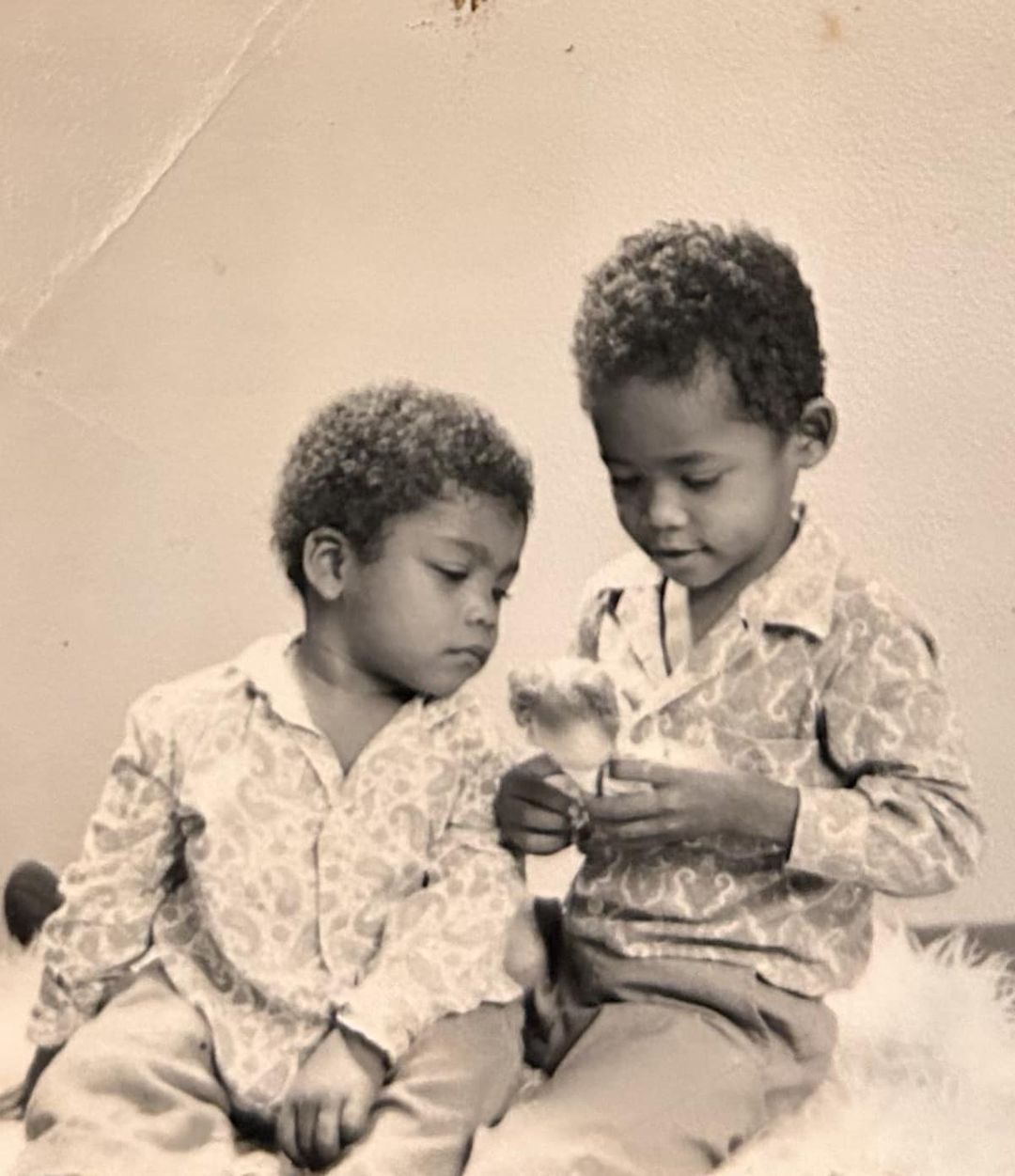

Damian shares about a different type of reunion, not with biological family but with an adopted sibling who got returned to the State in Australia.

-

Finding Peace after Adoption

—

by

in Abuse in Adoption, Adjustment and Transition, Adoptee Anger, Adoptees Educate, Adoption Education for Adoptive Parents, Adoption Education for Professionals, Australia, Complexities in Adoption, Critical Thinking in Adoption, Family Preservation, Grief and Loss, Haiti, Importance of Connections to Origins, Is adoption the best option, Lifelong Impacts of Adoption, Not Knowing in Adoption, Older Age Adoptions, Origins Search, Racism in Adoption, Search and Reunion in Adoption, Sense of Belonging, Therapy, Transracial Adoption, Trauma in AdoptionJonas shares on the complexities of being an intercountry adoptee, ending up on the streets at age 13 and getting his life back as an adult to find his peace.

-

Adopted from India to Belgium

Annick shares her thoughts on being adopted from India, marrying another adoptee, having a child of her own.

-

Trauma of Transition for Older Aged Adoptees

—

by

in Adjustment and Transition, Adoptee vulnerability, Adoptees Educate, Adoption Agencies, Adoption Attachment, Adoption Education for Adoptive Parents, Adoption Education for Professionals, Adoptive Country, Birth Country, Critical Thinking in Adoption, Grief and Loss, Importance of Connections to Origins, Is adoption the best option, Lifelong Impacts of Adoption, Not Knowing in Adoption, Older Age Adoptions, Sense of Belonging, Transracial Adoption, Trauma in AdoptionOlder age adoptees struggle to transition from their first life to their second. What can be done to reduce the trauma of transition in older age adoptions?