Tag: privilege and colonial structures in adoption

-

An Adoptee’s Thoughts on Haaland vs Brackeen

—

by

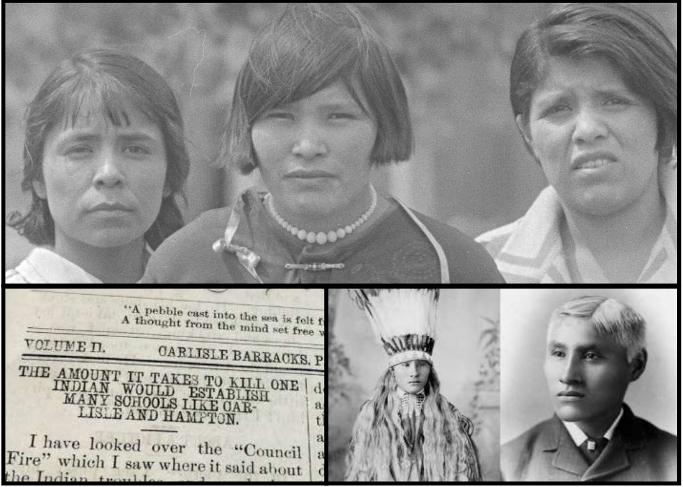

in Adoptee Activism, Adoptees Educate, adoption reform, Complexities in Adoption, Critical Thinking in Adoption, Family Preservation, Grief and Loss, Impacts to Biological Families, Importance of Connections to Origins, Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), Is adoption the best option, Lifelong Impacts of Adoption, Rights in Adoption, South Korea, Transracial Adoption, Trauma in Adoption, USAPatrick shares on the current Haaland vs Brackeen case that challenges the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) and asks why family preservation isn’t the focus.

-

My View of Adoption has Changed with Time

Maria shares how her views and understanding of adoption have changed over time as she’s connected herself more to the adoption community and educated herself.