#2 ICAV Blogger Collaborative Series from Adoption Awareness Month 2019

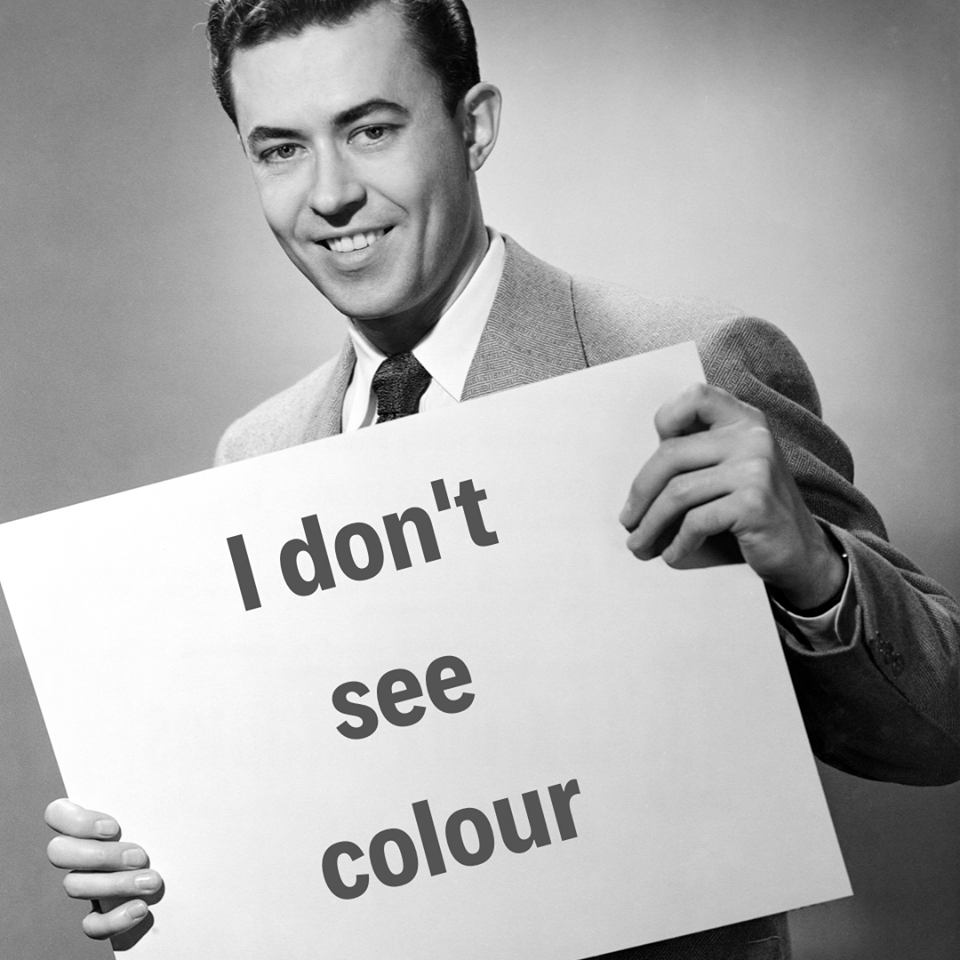

When someone says “I don’t see colour,” to me this means they don’t see me. They will argue that they see me as a “person,” just like we are all people. But I counter that view because my personhood, my identity, my humanity, cannot be uncoupled from my brown-ness.

Pretending not to see colour has the effect of negating everyone’s ancestry, personal and familial history, and their lived experiences in the racialised society we all live in – no matter where we live. In intercountry adoption (ICA), this “colourblind” view can be absolutely devastating because ICA is dominated by white people adopting brown and black babies from all over the world. If white adoptive parents refuse to see their child’s skin colour or their own skin colour, how can they fully parent and love their child unconditionally?

For, it would seem, being colourblind is only possible under certain conditions: (a) I don’t have to see your colour; (b) I don’t have to acknowledge my colour; (c) we never have to talk about what your colour or my colour means; (d) we never, ever have to talk about how those colours exist in relation to each other within the larger context of culture and society.

From the perspective of a brown intercountry adoptee like me, I feel a mixture of sadness and anger towards anyone who espouses a colourblind mentality because they essentially negate the history of my brown ancestors.

If you refuse to allow that humanity has attached certain assumed behaviours and levels of privilege and importance to different skin colours, how can we possibly have a conversation on why these structures are in place, who’s benefitting and who’s being harmed by them, and why it’s important to create a truly level playing field?

When white adoptive parents pretend to be colourblind, how can they help their child be proud of the skin they’re in? How can they recognise their child’s need for racial mirrors? How can they help their child understand the beautiful and rich aspects of the child’s ancestry and culture as well as the pain and oppression their race has experienced and continues to experience, and how those dynamics relate to each other? How can they help nurture a racially competent child who grows up into a racially competent adult – even if that means their son or daughter is racially competent in a race that doesn’t match their own? How can they see the role that their white privilege has played throughout their own lives and via the intercountry adoption of their child? How can they decide how to use their white privilege going forward?

None of this is possible if we are teaching and encouraging people, including white adoptive parents, to pretend not to see colour.

von Abby Hilti

Congratulations you’ve just completely erased my first culture, my birth family, my genetic history, my country of origin! Look I know you meant well, but underneath this, there’s an insensitivity or lack of awareness about everything that I was and still am before I was adopted. It’s kind of like you’re saying, “Good job – you have assimilated so well that you’re just like me/us now!” But I’m not.

One of my fellow intercountry adoptee friends joked about how we are coconuts – brown on the outside and white on the inside. It’s funny, but it’s also not funny.

My adoptive parents tried to show me books and documentaries about Vietnam when I was growing up, but I wanted nothing to do with anything that highlighted my difference. When I got sunburnt on my nose, I asked mum if I’d be white underneath. So I got caught up in the “not wanting to see my colour thing” either.

I was very good at being a chameleon, it’s like I had to become one to survive. I was so desperate to fit in and to belong that I learnt fast about how to adapt my personality to be loved and liked. I still do this to this day, but I’m learning that I’m enough as I am and I don’t need to perform to be worthy of being loved.

von Kate Coghlan

The popular TV show This Is Us wowed audiences again with its coverage of transracial adoption. I don’t watch the show, and a lot of adoptees can’t bring themselves to watch it either. And yet it’s immensely popular with adoptive parents. The supposedly “mic drop” scene is as follows:

Jack: When I look at you, I don’t see colour. I just see my son.

Randall: Then you don’t see me, Dad.

During NAAM, it’s particularly biting to see this interaction getting mainstream attention. You see, many of us adoptees of colour have had this exact dialogue with our colourblind families and friends (myself included).

This isn’t an original line, and dare I say, I wouldn’t be surprised if the writers lurk in adoption spaces and stole this from the stories of adoptees, co-opting our stories for better ratings.

This isn’t some TV script for your entertainment; this is a painful part of our real lives. It hurts us in deep, existential ways to be denied access to our birth culture and traditions and then to be unseen by our adoptive families. It is actively rejecting us a second time.

If you refuse to “see” the parts of me that are a brown Indian, then you are actively refusing to support me on my journey to discover who I was born to be. Your choice to take the easy road to claim, “I’m not racist” actively isolates me and in turn plays into its own racial problems. Take the harder road with me, with any of the people of colour in your lives, and learn how to unlearn racial biases. This work requires you to see, so take off your (colour)blinders.

The fact that it takes a network TV show to get this concept to take hold rather than the direct words of real adoptees should disgust anyone and everyone who loves an adoptee.

I challenge adoptive parents and allies who support the adoptee attempt to “flip the script” during NAAM to think about how prioritising entertainment over the real words of adoptees is its own form of silencing; to be more intentional about whose voices you choose to uplift; and be more critical of the media you choose to consume.

#NotMyNAAM

#NAAM

#FlipTheScript

#adoption

von Cherish Bolton

Somewhere along the way in my life, I got the message that I’m not a real Asian. As a mixed race adoptee I don’t even dare try to join Chinese adoptee communities or Indian ones for fear of not being enough in some way. I can’t make sense of what it is to be a Malaysian Chindian — I don’t know any others, I’ve never met one. There are no books I know of, no museums or movies. Even if there were, I would be reading them the way an outsider learns about history.

Something I resent is the suggestion I should do something in order to belong. Belonging isn’t a citizenship test!

As an intercountry adoptee brought to England by a white couple with no friends of colour, all the markers of my culture have been erased. Except my skin colour, my hair, it’s texture, my eyes. Each time someone says, “I don’t see colour”, or simply behave as though they don’t, this implicit message that I don’t belong in my biological culture is reinforced and I’m erased a little more.

I don’t forget that my gay friends are gay, I don’t forget their struggle to belong or to feel safe holding hands or kissing in public. To erase that would be a failure of empathy and allegiance. Of course it isn’t the only part of their identity and I’m interested in all the other parts too. The ones that are like me (or not), the parts that amaze, amuse or confuse me — I love them all.

Everyone just wants to be seen. I wonder what makes you feel unseen?

When we experience ourselves differently to how we are seen, there’s a disconnect, a disruption to our identity which isn’t resolvable with free will alone.

Belonging is relational – by its very nature it demands the acceptance of others.

von Juliette Lam

Since the later years of coming to terms with my identity, fitting in between my two worlds (adoptive and birth), understanding the impacts of being relinquished and adopted, I have shared many of my experiences to wide audiences but one situation close to me, never ceases to frustrate me the most. This is when my own adoptive family make this comment, “But we see you as one of us” or “We don’t see you as being different” after trying to explain how I’ve always felt so different and out of place.

I acknowledge, in their eyes, they are trying to say to me that I am accepted and embraced by them as being one of their “clan” despite my skin colour and outward obvious differences. But without any in-depth discussions about the complexities of being intercountry adopted, these types of comments just made me feel even more disconnected and isolated from them. What it showed me was they had very little understanding of my intercountry adopted journey. When they don’t have these important conversations with me, they are oblivious to how their comments make me feel even though I know it is not what they intend.

What would I prefer my family to say? I would prefer them to acknowledge my differences and really try to understand where I’m coming from. For me it’s about the discrepancy I experience on a daily basis because strangers throughout my life meet me once and make basic assumptions that I am NOT one of them (white Australian) based on my appearance – my skin colour, my eyes, my hair. The internal battle I face as an intercountry adoptee, is that whilst in my private family circles I might be fully accepted, it is NOT the experience I have in public outer life.

The constant jarring reminders of “not belonging” in my wider adoptive society leaves me with a lot of unresolved questions of who I am, where do I belong, who are my clan, and how did this reality eventuate. Are my adoptive family even aware of these impacts? No because they are so blind to what everyone else can see and received very little education on race, culture, and the importance of open discussions. Ignorance is not bliss in this case.

So when my adoptive family says, “I don’t see your difference, you’re one of us” when clearly I’m not as clarified by many strangers, this comment only acts to shut down the conversation instead of opening it up and allowing me the space and love to process competing realities.

Being intercountry adopted is not a reality we adoptees can ignore for too long!

von Lynelle Lang

I don’t know if it’s the fact that I didn’t grow up in an English-speaking country, but we don’t use the word “colour” to describe a person. In Sweden, we use “foreigner” as opposed to being Swedish. So instead of saying “I don’t see colour”, people would say “I never think of you as anything but Swedish” or “I see you as the same as us”. They say that to be nice.

When I grew up there were very few people in Sweden with a darker complexion. Most didn’t speak the language well and some of them (of course, a small minority) appeared shady. Swedish mindset is to question if they (dark complexion people) could be trusted.

To tell me that I don’t appear foreign means I am a person they trust. But … when I go on dating sites strangers viewing my profile, only see colour. I get less guys who write than my white peers, less matches with white skin but more super likes from “foreign” men.

One time I wrote in my profile text that I was adopted so as not to appear scary. Then I thought adopted might also sound scary, because in Sweden that implies psychological problems. So I deleted it again and had to come to terms with being less popular online.

My close friends have never said these words to me about not appearing foreign but I do things said like this occasionally and every time, I am offended. As if that random person has a right to put an approval stamp on me. As if I were to do anything untrustworthy, he or she would judge me much harder and say, “Hmm, I guess she wasn’t like us, after all”.

von Sarah Mårtensson

What defines me is not what you see, it’s what I see. Colours don’t colour my life, but my experiences in a prejudiced and bigoted society have.

A transracial adoptee’s worth as a human being is both legally and socially determined by his adoptive parents, his adoptive family, their friends and neighbours, and the entire local community that is encouraged to invite him in as one of their own. But as I eventually learned the security blanket of immediate family didn’t always save me from explaining what I was doing there or defending how I belonged. In my youth, it seemed like I was constantly feeling a barrage of disconcerting interactions with other kids who called me out, in so many words, as being a foreigner, even though I knew nothing else than what my Irish Catholic family had taught me: That I was an “Allen”, that I had to go to Mass every Sunday, that I spoke English and that I belonged to them.

The erasure and then replacement of my identity reverberated in how I developed a sense of self: I didn’t really have a Self. I had a mock-up of one, a misfitting template that I was encouraged to carry around and display each and every day. I didn’t know what it meant to be Vietnamese because that was not the point of this whole adoption experiment. I was trained to look in the mirror and pretend that I was just another Irish Catholic kid with a bad temper. I was trained to not read about the war I had been exfiltrated from. I was trained to see myself like everyone else.

I even trained myself not to see colour. Even though my graduating class in high school comprised many kids from refugee families from Southeast Asia as well as several Asian adoptees, including me, I couldn’t pick them out because I refused to see them other than strangers. I didn’t hang out with any of them or even talk to them because why would I? I was “Kevin Allen”. Son of Evalyn and Bob, and oldest brother to two sisters. I couldn’t even find myself for so long because I was lost. Lost in the fantasy that I was just like my parents, just like my aunts and uncles and cousins, and just like the community that held me under its tutelage.

In art studio class in high school we had to do a self-portrait. I took my time drawing mine. I used coloured pencils and got the shading and features of my young face all correct and flattering. I thought it was a great representation of me. It was one of my proudest works. But I never kept it for myself. I gave it to my parents. I felt I had no use for it.

von Kevin Minh

Hinterlasse eine AntwortAntwort abbrechen