标签: older age adoption

-

A different type of Reunion

Damian shares about a different type of reunion, not with biological family but with an adopted sibling who got returned to the State in Australia.

-

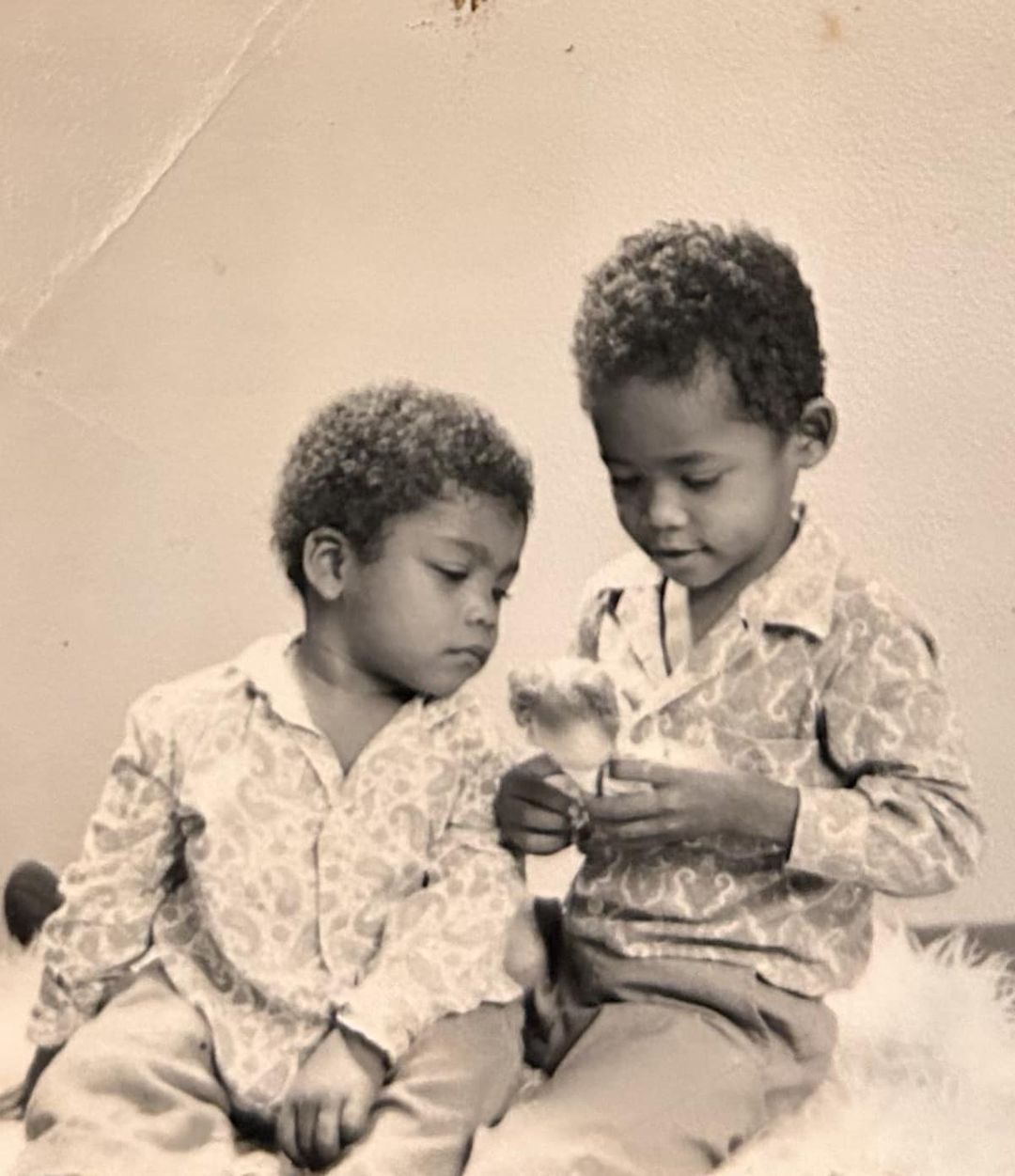

A Life has been Lived Before Adoption

—

由

于 Adjustment and Transition, Adoptees Educate, Adoption Education for Adoptive Parents, Adoption Education for Professionals, 澳大利亚, Critical Thinking in Adoption, 埃塞俄比亚, Grief and Loss, Importance of Connections to Origins, Lifelong Impacts of Adoption, Older Age Adoptions, 跨种族收养, Trauma in AdoptionMeseret shares about the complexities of being adopted at an older age, having memories of life before adoption, learning how to trust her new adoptive family.

-

收养后寻找和平

—

由

于 Abuse in Adoption, Adjustment and Transition, Adoptee Anger, Adoptees Educate, Adoption Education for Adoptive Parents, Adoption Education for Professionals, 澳大利亚, Complexities in Adoption, Critical Thinking in Adoption, 家庭保全, Grief and Loss, 海地, Importance of Connections to Origins, Is adoption the best option, Lifelong Impacts of Adoption, Not Knowing in Adoption, Older Age Adoptions, 起源搜索, Racism in Adoption, Search and Reunion in Adoption, Sense of Belonging, Therapy, 跨种族收养, Trauma in AdoptionJonas shares on the complexities of being an intercountry adoptee, ending up on the streets at age 13 and getting his life back as an adult to find his peace.

-

Remembering Origins

A few days ago, I was invited to attend the filming of Sarah Henke to cook with a famous TV Chef from Korea 전현숙. He came to Germany to interview Sarah, a KAD chef who works at a restaurant and recently earned the coveted Michelin Star. During the filming of the program all guests were…

-

Trauma of Transition for Older Aged Adoptees

—

由

于 Adjustment and Transition, Adoptee vulnerability, Adoptees Educate, Adoption Agencies, Adoption Attachment, Adoption Education for Adoptive Parents, Adoption Education for Professionals, Adoptive Country, Birth Country, Critical Thinking in Adoption, Grief and Loss, Importance of Connections to Origins, Is adoption the best option, Lifelong Impacts of Adoption, Not Knowing in Adoption, Older Age Adoptions, Sense of Belonging, 跨种族收养, Trauma in AdoptionOlder age adoptees struggle to transition from their first life to their second. What can be done to reduce the trauma of transition in older age adoptions?

-

一个年长被收养者的回忆和感受

—

由

于 Adjustment and Transition, Adoptee vulnerability, Adoptees Educate, Adoption Agencies, Adoption Attachment, Adoption Education for Adoptive Parents, Adoption Education for Professionals, 澳大利亚, Complexities in Adoption, Critical Thinking in Adoption, Importance of Connections to Origins, Is adoption the best option, Lifelong Impacts of Adoption, Older Age Adoptions, Sense of Belonging, Thailand, 跨种族收养, Trauma in Adoption在年长时被收养会带来更复杂的问题,需要解决并需要专门的支持。敏分享了她作为泰国被收养者的故事。